Foreign ISIS women on hunger strike in Baghdad Prison

As Ramadan ended on Friday, April 21, foreign ISIS women serving prison sentences in Baghdad’s Rusafa prison began a hunger strike. They have only one demand. They want their freedom.

As Ramadan ended on Friday, April 21, foreign ISIS women serving prison sentences in Baghdad’s Rusafa prison began a hunger strike. They have only one demand. They want their freedom.

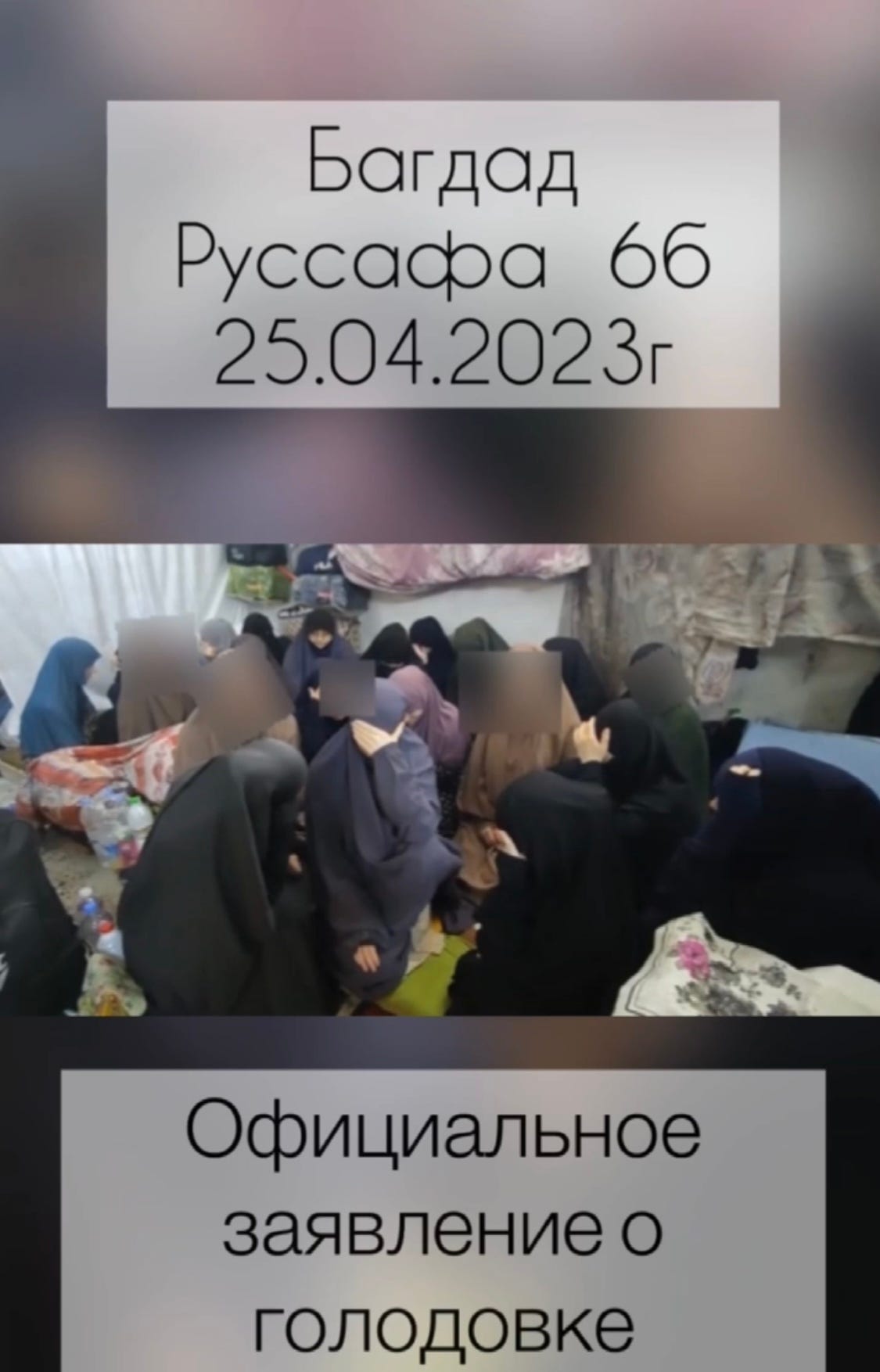

It began when several inmates from Russia, Belarus, and Tajikistan started a hunger strike. By the next day, information about the strike had spread all over prison and they were soon joined by other foreign women, first those from other former Soviet Union countries and then women from Turkey.

One strike participant from Dagestan, sentenced to 20 years for terrorism, explained how news spread. “During the daily walk in the yard, women asked us why we were doing it [the strike] and now our ranks are increasing. We get messages like ‘Cell 15 and 16 is joining us’ and ‘Several women from cell nine have also stopped eating.’” The majority of these women are only refusing food, but there are some who also refusing water. Though prison guards continue to bring food and leave it outside the cells, so far it has remained untouched.

When the ISIS women were arrested after Tal Afar, the last ISIS stronghold in Iraq liberated by Iraqi military in 2017, they were sentenced to varying prison terms ranging from five years to life in prison. The prison houses several hundred women from a dozen countries including former Soviet Union, France, Syria, Turkey, Sweden, Germany, and Trinidad. Some of them even continue to support ISIS using contraband cell phones to spread ISIS propaganda and coordinate money transfers between group members outside the prison.

Several years ago, the majority of children belonging to these women were repatriated and reunited with their relatives. And this year those inmates sentenced to five years (three Tajikistan nationals and three Russian nationals) were released and returned to their home countries. Those women who remain behind bars with longer sentences see this as unfair and are demanding to be repatriated. Inmates have recorded several video addresses where, with blurred faces, they demand to be released. They say they were wrongfully convicted of terrorism, gave statements under pressure from Iraqi security services, and did not have access to lawyers.

They also complain they have no visitation from family members and are separated from their children. They also mention food quality and the absence of medical services, which are indeed major problems in Iraqi prisons. Inmates from Azerbaijan and Turkey made a video in their language addressing their government. “Either take us home or we will die here,” said Russian-speaking women in her video address.

But these videos are not only addressed to the home governments of these women. They have already been widely circulated by ISIS telegram channels with a hashtag #RusafaLibre and have already been reedited to include ISIS nasheeds (music) and slogans about the urgent need for ISIS to liberate that prison.

It is possible that their sentences are disproportionally long for the crimes they committed, but being adults when they joined the group, those women understood Iraq’s harsh laws for membership in terrorist organizations. At the same time, the conditions in Iraq’s prisons are clearly in need of improvement. And this is the case not only for the foreign women who are serving their sentences actually in much better conditions then Iraqi inmates, but for all inmates in the country.