Journalists needed... for Russian propaganda.

Alexander Dugin-affiliated Eurasian Movement is organizing propaganda tour to Russian occupied Eastern Ukraine and invites journalists. All expenses covered and exclusive content promised.

Russia desperately wants to sway international public opinion, and the most effective way to do it is though journalists and influencers. So in addition to their own media outlets like Sputnik and Russia Today, they want to attract more independent (and international) journalists that will project their point of view.

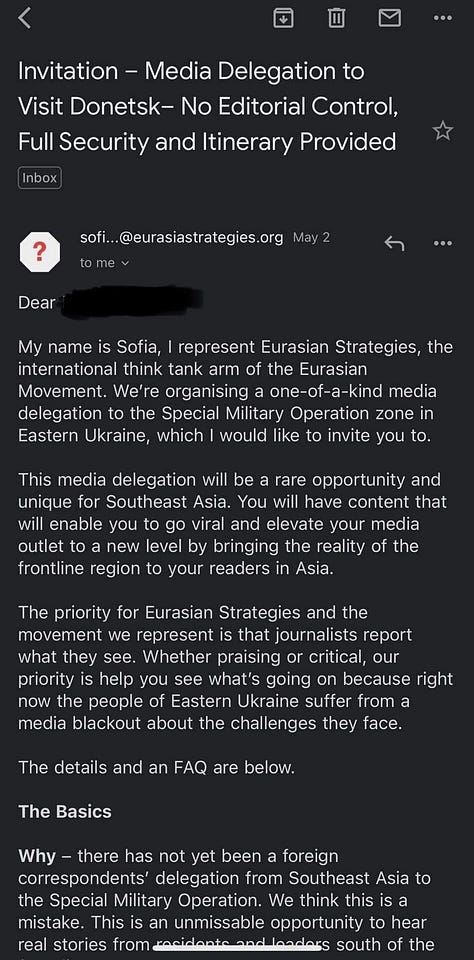

In the beginning of May, journalists from Southeast Asia received an email inviting them to a “one-of-a-kind media delegation to the Special Military Operation zone in Eastern Ukraine.” The email was from an Alexander Dugin-affiliated Eurasian Movement in Russia and its international arm, Eurasia Strategies.

According to the email, the main selling point of the media tour is “content that will enable [journalists] to go viral and elevate [their] media outlet to a new level.” The whole tour, including round trip transportation from each journalist’s home country, is free of charge and even includes per diem pay.

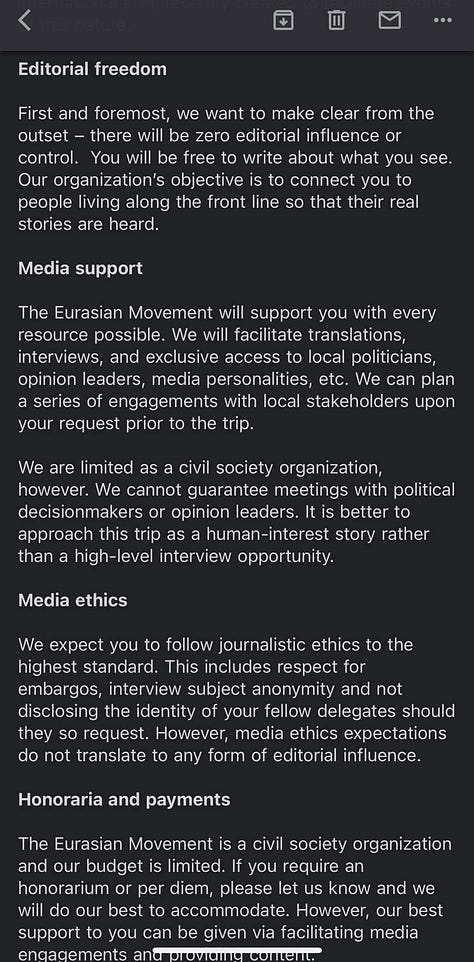

The tour is planned to begin in Moscow. Journalists will then be taken to the Donetsk, Lugansk, Kherson, and Zaporozhe regions where interviews with local residents and political leaders will be facilitated. Tour organizers will also provide translation, security, interviews, and exclusive access to local politicians, opinion leaders, and media personalities. The email also mention being able to “plan a series of engagements with local stakeholders” upon prior request.

The email also includes an official reason for the tour: “There has not yet been a foreign correspondent delegation from Southeast Asia to the Special Military Operation. We think this is a mistake.” However, the trip’s main objective is to highlight Russian propaganda about Ukraine’s alleged crimes in the Donbas region, as the email states the tour’s “priority is to help [journalists] see what’s going on because right now the people of Eastern Europe suffer from a media blackout about the challenges they face.” The email also mentioned the media tour should be approached “as a human-interest story rather than a high-level interview opportunity.”

Trying to present itself as a legitimate Western- style organization, the Eurasian Movement also highlighted their commitment to journalistic ethics. The email reads, “There will be zero editorial influence or control. You will be free to write about what you see.” Even the issue of faith is broached, assuring potential participants that “Russia is a multifaith nation” and that the “Eurasian Movement is made up of members from all religious backgrounds, and we respect faith in God to the utmost extent.”

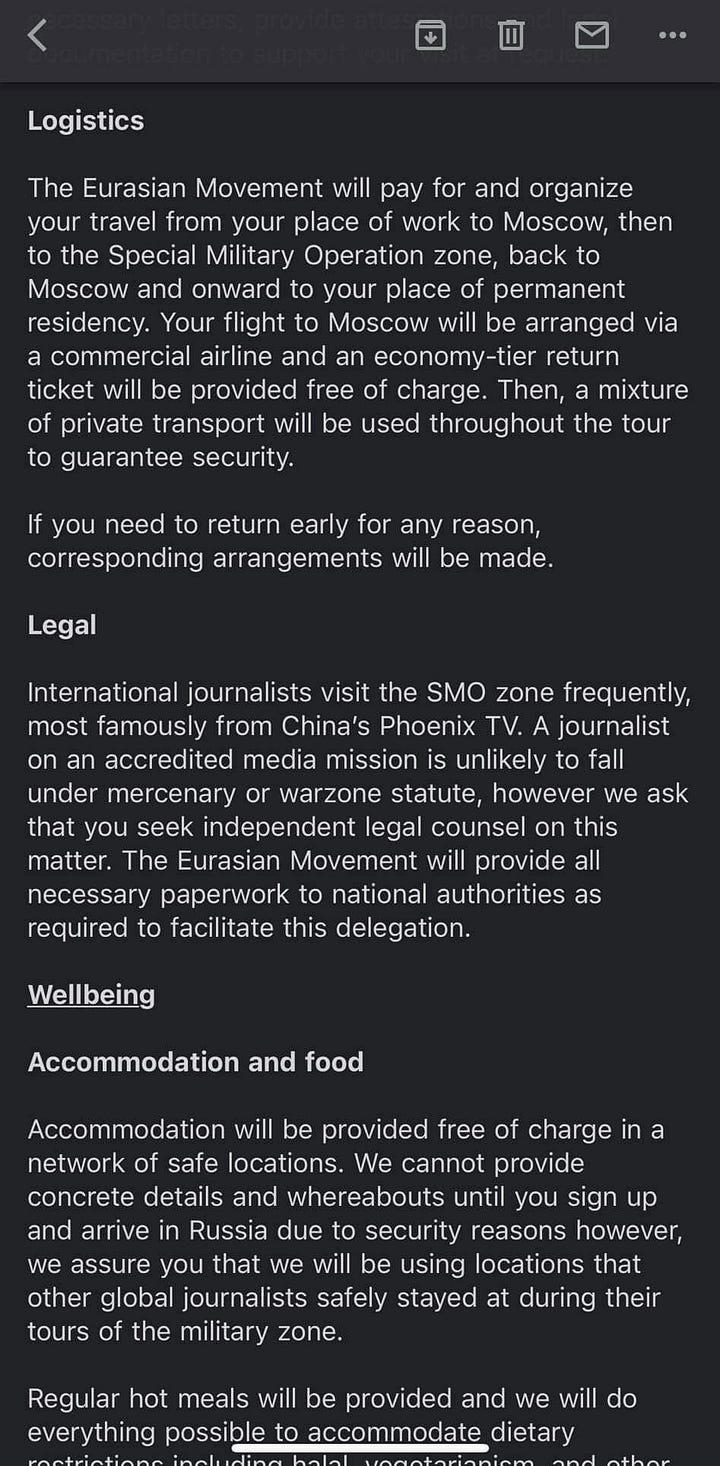

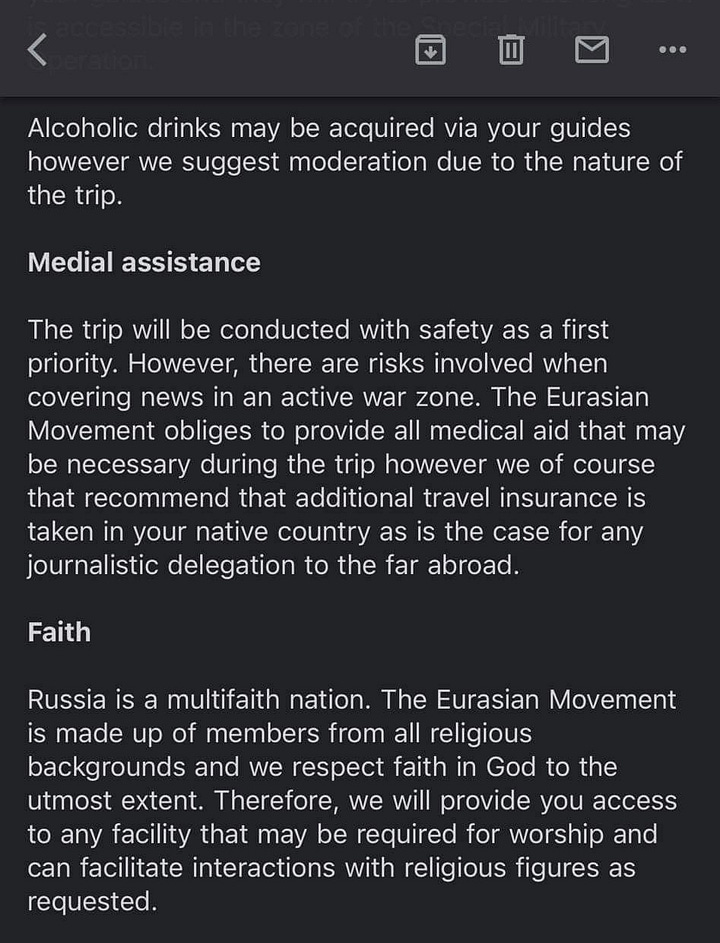

Of course the issue of legality could not be ignored, so potential participants are assured the media tour will not fall under mercenary or warzone statutes and, if needed, the necessary paperwork would be provided to national authorities. The email then cites China’s Phoenix TV as an example of an international media outlet freely working with no legal repercussions in Russian-occupied Ukraine.

Interestingly, the dates for the tour will not be revealed to participants until after they sign a non-disclosure agreement. Disclosing the identity of fellow journalists is also not permitted.

For Russia, organizing such media tours is not something new. They’ve done it for years in Syrian pro regime territories. But the trips were not particularly effective when Western journalists were invited. Both journalists and their audiences assume that a Russian-curated itinerary usually means exposure only to what is meant to be seen. However, such a tour for journalists from developing countries may prove to be more effective for three reasons.

First, the population of the recently invited countries are more pro-Russian to begin with. Second, the only other way for these media organizations to report from the field is by sending their journalists to Ukraine themselves, something that is cost-prohibitive. And not only it is expensive to maintain a journalist there ( around $500 per day), entering Ukraine now requires several hard-to-get visas (including a Schengen visa).

It is up to each invited journalist whether to take part in such a propaganda trip, but just the existence of such a tour reveals a major problem in international media that Russia is exploiting. If the West does not want Russia to be the main voice informing the media in developing countries, they should support local journalists not only in domestic coverage, but also the coverage of international news.